Rod Serling attempts to run the conventional Western out of town, but finds he must go it a “Loner.”

By Tony Albarella

“In the aftermath of the bloodletting called the Civil War, thousands of rootless, restless, searching men traveled west. Such a man was William Colton. Like the others, he carried a blanket roll, a proficient gun, and a dedication to a new chapter in American history…the opening of the West.”

This passage precedes what is perhaps the most existential, and ultimately obscure, television Western ever produced. The Loner centered on the exploits of a battle weary and introspective ex-Union cavalry captain named William Colton, who worked his way Westward in search of himself.

With a focus on characterization and philosophy the series was as unconventional as they come. From the outset it had everything going for it: a proven film and television star in Lloyd Bridges to helm the lead role, a wealth of capable guest stars, established and respected directors, even a catchy theme song by renowned composer Jerry Goldsmith. The project had an equally strong foundation; it was conceived and written by none other than Rod Serling, fresh off the successful network run of his legendary Twilight Zone series.

Prior to his Twilight Zone years (1959-1964), Serling was already thoroughly entrenched in the craft of writing television. He bore witness to its birth and had sold well over 60 teleplays before ushering us into that “dimension of imagination.”

Several smash anthology hits including “Patterns,” “Requiem for a Heavyweight” and “The Comedian” placed Serling among the upper echelon of small screen playwrights. Along with fellow visionaries such as Paddy Chayefsky and Reginald Rose, Serling defined the fledgling medium and showcased television’s dramatic potential. The coveted Emmy for Dramatic Writing was awarded to Serling six times, the most of any television writer, a record that stands to this day.

It was, however, the writer’s well documented battles with sponsors and censors alike that led to the creation of The Twilight Zone. Program sponsors were concerned exclusively with product exposure and profit margin, and they constantly expressed concerns over program content. The censors followed suit by vetoing anything they deemed objectionable to the masses.

Serling’s penchant for controversial issues invariably burst through these tight boundaries, and the writer and the powers-that-be would clash with frightening regularity. Realizing the futility of this fight, Serling found that if he masked his morality plays under the guise of fantasy and science fiction, he could bring his points home “under the radar” of the television executives.

In the context of the running threads that wove his overall body of work, The Loner is not all that surprising a creation for Serling. It revisited many of the themes prevalent in his earlier writing: the horrors of war, moral ambiguity, bigotry, and the pressures of command and responsibility.

Yes, writing a typical television Western shoot-’em-up was a capitulation to the network, but so was Twilight Zone from a certain point of view. In essence both series were vehicles which attempted to slip unconventional concepts into the realm of an acceptable television show format. Besides, when compared to other television Westerns, The Loner proves to be anything but typical.

Serling’s move to the Western was almost as unexpected as his move from pure drama to fantasy fare. It was also panned by critics who didn’t grasp the network mentality as Serling did. TV Guide critic Cleveland Amory began his review of The Loner with the following: “Rod Serling, who has done some fine things on TV, evidently felt there was a crying need for another TV Western.”

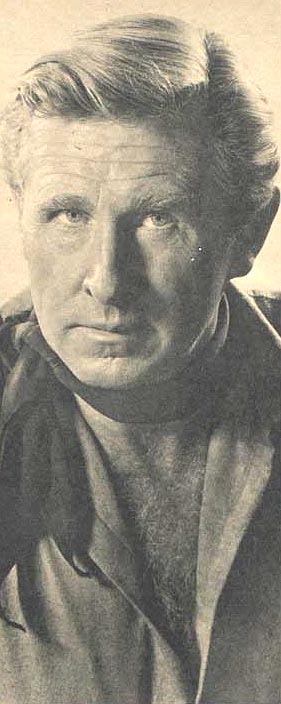

Lloyd Bridges starred in “The Loner”

By the mid-sixties the television Western was a genre that had been well mined. For over a decade frontier stories had been explored and every scenario involving a gun and a horse had been played out. But it was still a tangible format to the networks; one that came not only with a targeted audience and a guaranteed return but also with a minimum of risk. Serling understood this and, much like with his migration to the fantastic trappings of The Twilight Zone, brought his stories of right and wrong to the Civil War era.

James Aubrey, CBS programming executive

The origin of the show dates back to the first season of The Twilight Zone. James Aubrey, the head of CBS at the time, was presiding over a network transition from live television drama to a more lightweight schedule, dominated by situation comedies and game shows. Friction between Aubrey and Serling resulted as the writer watched his beloved live anthologies fall victim to the network axe.

Aubrey also developed a reputation as a detractor of The Twilight Zone, which he frequently chastised for budget overruns. With the handwriting on the wall, Serling assumed it probable that CBS would not renew his series and wrote a one-hour pilot about a Civil War hero that heads West in a quest for meaning and enlightenment.

While CBS turned down the concept, they also gave The Twilight Zone a green light for the 1960-61 season. William Dozier, production head at Screen Gems, read and enjoyed The Loner script, as did producer William Self, who had successfully collaborated with Serling on “Where is Everybody?” – the pilot show for The Twilight Zone. However, with Serling’s attention again focused on The Twilight Zone, the script was shelved…gone, but not forgotten.

By 1965, The Twilight Zone had been cancelled and Dozier was the head of his own production company, Greenway Productions, named for the Beverly Hills street on which he lived. While he had no luck peddling sitcoms, Dozier discovered that the Western was again in vogue with the networks. Greenway had set up shop at Twentieth Century-Fox, where William Self was now head of television production. Both men remembered Serling’s Western pilot and the hunt was on.

“I don’t think we had any Westerns on at that time,” recalls William Self. “I remembered this notion that Rod Serling had. And I called Rod, and he was excited that he finally had a chance to do it.”

At the time Rod Serling was in the midst of an 11-week tour of Hong Kong. Working with the State Department, Serling had hit the lecture circuit, extolling the virtues of television and U.S. foreign policy. The last thing Serling must have expected at the time was a call from William Self, asking about the feasibility of a new series based upon his Loner concept.

Llyod Bridges in “Sea Hunt”

“I thought it was a pipe dream,” Serling told Fritz Goodwin in an interview with TV Guide. “Who was going to buy a show that had been lying around for more than four years?”

Dozier wisely had the foresight to use some star power in casting the main character of William Colton. Chosen to portray the meandering cowboy was an actor with a large measure of television success in his own right. Millions knew Lloyd Bridges as Mike Nelson, the adventuresome frogman star of Sea Hunt, which ran from 1957 to 1961. After donning the scuba mask for 156 shows (ironically the same episode total as Twilight Zone), Bridges was rewarded with his own self-titled series. However, The Lloyd Bridges Show was canceled after a single season in 1963.

“I was terribly disappointed when The Lloyd Bridges Show didn’t make it,” the star confessed to Harold Stern of the Chicago Tribune. “I had my mind made up I wasn’t going to go through it again. I turned down a few series because I was convinced that doing another would be madness. But along came Rod Serling and I couldn’t resist.”

Llyod Bridges and Rod Serling

Bridges had the talent and rugged good looks to pull off the character of Colton, and he and Serling meshed well together. The fact that Bridges was blacklisted briefly for political activism during the height of the McCarthy era only added to the chemistry between the actor and the outspoken writer.

“Rod Serling was the main reason,” Bridges responded when asked about his decision to again tackle a television series. “With him doing 75 percent of the scripts and Bill Dozier producing, I knew I’d be in a quality show.”

Not only did Dozier lack a pilot film when offering the idea to CBS; he forged ahead without so much as a written presentation. He hitched his wagon to the star status and name recognition of Bridges and Serling, respectively. CBS went for it.

“Serling was still, and remained, a big name,” says Self. “And one that CBS in particular had a lot of affection for. I think it was the combination of Serling and the script that just kind of made it happen.”

To add to the irony, the decision to carry the series was made by none other than James Aubrey, the very executive that had cast The Loner aside four years earlier. Less than a week after approving the series, Aubrey was fired as president of CBS-TV.

Rod Serling returned from overseas to find the deal inked. The Loner was sold as a half-hour series with Serling as lead writer and executive script consultant. His contract required that he write a minimum of seven of the first 13 shows.

The agreement called for 26 shows, with a cutback clause after 13 airings. This stipulation allowed the series to be swiftly yanked in the event of a total ratings disaster. A 9:30 Saturday evening time slot was chosen, which did not bode well for The Loner. It was scheduled to run against ABC’s popular Hollywood Palace. This variety show was filmed in color, in an era when the novelty of such a broadcast was a great weapon in the publicity wars. The journey of The Loner was already proving to be an uphill ride.

Cayuga Productions, Serling’s company during The Twilight Zone run, was disbanded soon after the cancellation of that series. The corporation had been named for the tranquil Cayuga lake in upstate New York, the scene of many an idyllic vacation trip for the Serlings. With his summer home residing in the town of Interlaken, Serling looked to the same area in choosing a name for his new company. Thus Interlaken Productions was born and all the pieces were in place to begin work on The Loner.

In March of 1965 Serling left for Washington D.C. to debrief the State Department on the particulars of his Hong Kong trip.

“Television’s greatest weakness,” he said in his speech, “is its reluctance to take positions. Historically, during times of greatest stress, during periods of greatest controversy, the mass media are the first to be attacked, the first to be muzzled, and also unhappily-historically and traditionally-the first to fold up their tent and look the other way.”

Already Serling was pumping out scripts for his new show. The writer saw to it that in each show William Colton would confront significant, ethical issues that were as relevant in 1965 as they were a century earlier. The Loner would take a position, and stand by it.

During the trip home from that debriefing Serling suffered chest pains and was hospitalized. A family history of heart disease (Serling’s father died of a heart attack at the age of 52) was a leading factor in the decision to detain the writer for observation and testing. His stressful workload was of no help, nor was his four-pack-a-day smoking habit.

Eventually it was determined that the writer suffered from extreme exhaustion and he was released. Serling was allowed to continue his script writing chores on The Loner with the stipulation that he steer clear of on-the-set production.

As summer approached Serling had written a dozen scripts and production was under way. With space a premium on the backlot of Twentieth Century-Fox, the series had to be filmed at MGM.

15 episodes of the series were in the can by September, the start of the new television season. But all was not well behind the scenes and already looming were the storm clouds of network interference. Michael Dann, the senior vice president of programming at CBS, was not at all pleased with what he saw.

The premiere episode was entitled “An Echo of Bugles” and opened in a bar one month after General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Colton witnesses the bullying of a helpless Confederate veteran fresh out of a prison camp. A young, arrogant drunkard taunts the man for fighting on the wrong side and for having lost the war.

The teenaged bully spills the contents of a spittoon upon the very flag to which the Confederate soldier has pledged his allegiance. When the boy takes to beating the old man, Colton steps in.

“I don’t owe any allegiance to that flag either,” Colton replies when his loyalty is challenged. “But too many good men died for it to let me sit by and see it get desecrated by a little loudmouth who had no hand in bringing it down.”

After embarrassing the boy Colton is challenged to a draw, which he reluctantly accepts. As the confrontation nears, Colton relives the horrors of the war he has just left behind, including the stabbing of a young man not unlike his current adversary. Colton himself had been forced to kill the teenager when he was attacked on what turned out to be the last day of the war.

The duel takes place amid these various wartime flashbacks, and Colton wounds the gunfighter in the shoulder. Feeling relieved at having stood his moral ground without having taken a life, Colton takes his leave.

Prevalent here is the typical depth that Serling injects into his characters. There is no black and white but various shades of gray. Those fighting for the “good” side have become the villains while Colton protects a man that was his enemy only a few weeks prior. The true villain is revealed to be not a cause but a war, not a lack of pride but a lack of mercy.

The remorse that Colton harbors is poignantly expressed as he further explains his wandering quest. “The next death that I have a hand in,” he tells a colonel, “the next killing, if ever I have to kill again, I want it personal. I want to be able to choose. If some boy has to die at my hands I don’t want it sanctioned by an act of Congress, or my regrets ended by an armistice.”

Serling was apt at grafting onto characters his own wartime trials, which came in battles during World War II and forever haunted the writer. When the colonel asks why Colton plans to aimlessly drift after the war, his character’s reply might have been Serling’s in a different time and place:

“To try to get the cannon smoke out of my eyes, the noise out of my ears…maybe some of the pictures out of my head.”

Joan Freeman and Jack Lord in “The Vespers”

In “The Vespers,” Colton visits a friend and fellow ex-soldier, not for social reasons but to warn him of an impending attack. Now a reverend, Colton’s friend once killed two brothers, one of which had murdered an eleven-year-old girl, while acting as a deputized gun for hire. A third brother of the slain duo had sworn revenge and was now riding in to claim it.

Despite Colton’s plea the reverend refuses to resort to violence to protect himself and his pregnant wife. In a typical Serling soapbox speech, the reverend explains his reluctance to kill:

“I promised my God I would never again fire in anger. I would never again take a human life. I cannot turn my back on that promise, not if I want to call myself a man of God. Even when I shake inside with hate, even when I know that a gun, any gun, is an extension of my arm, a part of myself. And that I have a talent for killing that is so special and so perfect. Even then, with the knowledge that there are evil men who have no excuse for staying alive, I cannot break my pact with God.”

The attack begins, and Colton goes it alone against a group of five men. He takes a bullet in the arm and can no longer defend his friends. When the reverend’s wife is also wounded his instincts take over and he kills his persecutor.

While the reverend fears that he has broken his promise to himself and to God, Colton points out the difference between murder and self-preservation, and assures his friend that this unpleasant task was a necessary one.

“You took some lives tonight, reverend,” Colton tells him. “But you saved some too.”

Again we see that while several ingredients of the Western are adhered to, including gunplay in particular, it is moral conflicts and mortal limitations that drive the story. This is a tale that could play out in any genre and uses the Western merely as a setting and not as a plot device. The easy choices and well-defined roles of good and evil, so obvious in many cowboy shows of the fifties and early sixties, are nowhere to be found.

“The Oath” is a fine example of a character driven show with a relative lack of action. Taken hostage by a young fugitive, Colton and the owners of a boarding house soon realize their captor is gravely ill. He collapses and it is learned that he suffers from a near-ruptured appendix.

When Colton realizes a doctor is in the house, he attempts to fetch the surgeon. What he finds is a man drunk with whiskey and self-pity, victim of an accident that has severed both his right hand and his medical career.

“I might tell him how lucky he is,” the doctor says of the ailing fast gun. “When the appendix ruptures the pain goes away and the dying is quite quick and relatively painless…as opposed to my own which is tedious, extended and full of agony.”

Eventually the doctor agrees to guide Colton through the process and an emergency operation is performed. Although successful, the operation comes too late for the unfortunate fugitive and the man dies. However, the doctor realizes that his life can still have meaning and he sets out to teach his craft to others.

It’s not hard to imagine a programming director, well versed in the ways of the television Western, dismayed at an outing such as “The Oath.” The sparring in the episode is purely verbal, and the confrontations utilize words instead of bullets. It is entirely true that Serling’s style was frequently preachy and his prose purple. But the writer displayed throughout his career an uncanny ability to focus complex human traits and intricate philosophical concepts into streamlined scripts. Rarely can a cardboard main character be found, and it is easy to identify with the problems of most of his fictional creations.

Another facet of The Loner that differed from traditional fare is the ambiguous ending shared by a majority of the scripts. Most television drama ends with a complete resolution of conflict, all loose ends tied and all problems solved. In a format similar to that used on his Twilight Zone, Serling often concluded with downbeat endings, broken characters and finales that are left open to interpretation. Victories, while commonplace, are rarely clear or complete.

“These were powerful shows,” Cleveland Amory wrote in his review, “with realistic endings.”

For his part, Lloyd Bridges attacked the scripts with zeal. Emotional as well as physical stamina was required. The situations designed for William Colton often resulted in a demanding role for the actor, and Bridges lived up to the challenge. But the actor did voice some reservations regarding the main character.

“It has bugged me quite a bit,” Bridges admitted prior to the show’s debut, “that the guy doesn’t have any definite background, other than the Union cavalry – even more that he isn’t definitely headed anywhere. But Rod keeps telling me to let him worry about the character, just to trust him. And you know something? I do.”

All three of Bridges’ children guest starred on The Loner. Jeff Bridges played the title character in “The Ordeal of Bud Windom,” as the son of an accused killer. Beau Bridges also portrayed a title character in “The Mourners for Johnny Sharp,” the only two-part episode of the series. Both went on to become accomplished actors that are currently active and in demand. Cindy Bridges played a role in “Incident in the Middle of Nowhere.”

“Lloyd was a wonderful guy,” says actor Peter Mark Richman, who portrayed the father of Cindy Bridges’ character in “Incident in the Middle of Nowhere.” “We got more friendly afterwards. I knew Beau when he was just a kid. I recently ran into Cindy Bridges and we reminisced about the time she played my daughter.”

With the series premiere rapidly approaching, Serling met with Dozier and Dann after returning from a Labor Day sojourn at Interlaken. Dann was dissatisfied with the episodes he had viewed. Since the deal was struck without a pilot film on which to base his expectations, Dann presumably assumed that The Loner was to be a typical Western like countless others. It was not, and the executive wanted to know why.

Dann’s contention was that the series lacked action. While it is true that most of Serling’s scripts focused on conflicts of an internal nature, the writer argued that he was supplying what the network had agreed to. Emotion tension, he reasoned, was as marketable as physical violence. As with The Twilight Zone, Serling believed in the intelligence of his audience and refused to write down to the viewing public.

“What CBS bought,” Serling told the press, “was a series of 24-minute weekly shows – all legitimate, human, dramatic vignettes – set against a Western background. What they now want is a show with violence and killing attendant on a routine Western.”

In an interview for the PBS’s Rod Serling retrospective, “Submitted for your Approval,” Michael Dann explained his version of that infamous meeting and his vision of the show.

“I didn’t define action as seven bullet holes in nine people,” Dann recalls. “I really just wanted them to, I guess, ride around a lot more and save a lot more people or jump over a lot more houses and trees, but he said to me, ‘You don’t need any action in it. You just need characters you believe in and identify with’.”

Earl Holliman, William Self, Rod Serling

“CBS bought it,” William Self says, “thinking it was going to be much more of a traditional Western than it was. And I think that from day one we had a problem with the network. They didn’t feel we were delivering what we sold them and we felt we were. They just didn’t understand what we were selling, I guess.”

The star of the series also defended the concept of the show.

“I’d call it adult action,” Bridges said, “because the characterizations are so beautifully drawn. Serling can write believable characters. And I don’t think the character I play is just another guy looking for his identity. It goes deeper than that.”

Serling steadfastly refused to inject more violence into the show. As a result, production of The Loner was suspended before the series had a chance to hit the airwaves. With no network support the fate of the show would now be determined by ratings alone.

The Loner made its premiere on September 18, 1965. On October 11 the new season’s national Neilsen ratings were published and the series pulled a 15…a marginal showing, not spectacular yet not abysmal. With all that it had going against it, surely the show could not survive without stellar ratings. Serling and company prepared for a quick pink slip.

They were surprised, however, when Dann made an official announcement only two days after the ratings were released. The Loner was staying on the air.

While the decision was certainly made by committee, credit Dann with at least refusing to allow personal feelings to affect his decision. Surely the show would have been as much a historical footnote as its Old West setting if Dann had pushed for its cancellation. Instead it received a reprieve, at least for another 13 episodes, and production began anew.

At the reigns of the Western were several repeat-episode directors: Joseph Pevney, Alex March, Leon Benson, Allen Miner, Don Taylor, Paul Henreid and Norman Foster. Pevney in particular was well known and respected as a movie and television director, with a career that spans five decades and hundreds of shows.

Pevney directed the quintessential Loner episode “The Homecoming of Lemuel Stove”, which featured actor Don Keefer.

“The key to why I was in The Loner,” says Keefer, “had to do with the director, Joe Pevney. I had done several movies successfully with him and he asked for me.”

Pevney also directed the episode “Incident in the Middle of Nowhere,” in which Peter Mark Richman portrays a villainous actor.

“A very good director,” recalls Richman. “At one point in the production I added the soliloquy to Yorick, when he holds the skull, from Hamlet. This guy was a bad cat but he was a Shakespearean actor so I recited the thing from Hamlet, which was pretty effective in the film.” Pevney agreed, and the ad-lib made the final cut of the episode.

The series peaked with “The Homecoming of Lemuel Stove,” a compelling story about prejudice and honor.

“I thought,” says Don Keefer, who played a minister in the show, “it was a very, very intelligent, very good script. I thought the writing in that was especially good.”

The show begins with a scene straight out of Michael Dann’s textbook description of a Western. Colton is fleeing a raiding party of whooping, screaming Indians, all on horseback. Desert dust is flying, guns are blazing, and tomahawks are brandished with reckless abandon. A stranger who happens upon the scene assists our hero and proceeds to blow several Indians off of their horses.

With such a promising start, the next twenty minutes must have been seriously disappointing to Dann. The stranger is revealed to be Lemuel Stove, a black Union private returning to his father after three years of service. Both father and son are former slaves.

Colton asks his new friend if feels good to be emancipated.

“To be free?” Lemuel replies. “Yes sir. Far as I’m concerned that’s all there is, to be free and to be alive. One’s like the other.”

Together they ride to town and make a grizzly discovery. Lemuel’s father, branded “one of those uppity kind,” had been beaten and hanged the night before. The culprits were members of a pre-Ku-Klux-Klan unit, The Avengers, complete with white hoods.

The orphaned ex-slave vows to cut down and bury his father’s body, which hangs in the town square for all to see. Lemuel fully intends to be killed but plans to take down with him as many as he can. Colton pleads with Lemuel to allow the law to handle things.

“This is the only law there is,” says Lemuel, holding up a rifle. “The only jury around here that knows right from wrong. How come, Mr. Colton, your kind figures an ex-slave is less than a man, but you expect him to have the patience of a god? What’s the matter, Mr. Colton? Don’t it sit so good that there’s avengers on both sides?”

“It don’t sit so good, Mr. Stove,” Colton tells him. “And when the morning comes and the dead are cut down, I can’t distinguish one set of killers from the other. You looking for equality, Mr. Stove? Well, you’re down in a pit, eye level with snakes. And that’s a pretty low height for a man.”

After confronting the bigots, Colton and a minister help Lemuel retrieve the body. The Avengers attempt to stop them and both Colton and Lemuel kill a man. The rest of the pack flee. Lemuel’s father is cut down and it is revealed that the men had used bayonets and chains on his body.

“Where’s God, reverend?” Lemuel asks as he breaks down in tears. “Can you answer me?”

“Yes, Mr. Stove, I can,” replies the minister. “He’s been hanging here for more than a day.”

The minister prays over the body and turns his attention to Colton, and the two fallen men.

“Necessary, Mr. Colton, was it?” he asks. “This much death?”

“I’d like to find the answer to that myself,” Colton says sadly. “And I’d like to live with it.”

Clearly the subject matter was deeper and more profound than Dann or the network ever imagined when they bought the show. A more intense and adult Western would be difficult to find, and that was both the charm and the curse of the series as a whole.

“Serling’s approach to it as a Western,” says Self, “was a little more cerebral than the network was used to, and that was the issue with CBS. And they may have been right, it might have been more successful with more action.”

While ratings for the show remained steady, it failed to attract a larger audience in the months following its premiere. Tired of the resistance he faced daily, Serling grew increasingly pessimistic about the show.

“Right now it’s finger-pointing time,” the show’s creator said in December of 1965. “Everybody wants to put the blame on somebody else. And, as much as I hate to say it, I must assume a portion of the responsibility for what turned out to be a bad show. Some weekends, I wish Friday would move into Sunday and skip Saturdays so there wouldn’t be any Loner.”

Critical response to the show was mixed, and even the professionals had doubts as to how this esoteric mix of cowboys and contemplation could ever achieve the required amount of television viewership.

“Unfortunately,” notes Cleveland Amory, “what Mr. Serling obviously intended to be a realistic, adult Western turned out, judging from the ratings, to be either too real for a public grown used to the unreal Western or too adult for juvenile Easterners – we hesitate to say which. This is a pity because there are fine episodes here.”

In addition to these woes, the daily battles between Serling and Dann were taking their toll on the patience of both men. Serling made the regrettable decision to air his case in the court of public opinion.

“I told Dann,” Serling remarked to Harry Harris of The Philadelphia Bulletin, “that if the network wanted a conventional Western with an emphasis on violence and action, it should have hired a conventional Western writer.”

Dann was livid, and it was the final straw for the troubled series. The Loner was cancelled halfway through its inaugural season.

“Rod always went to the press,” Dann said. “He was probably, in the history of television, one of the most outspoken critics of the industry he was in. He never missed an opportunity to point out our weaknesses.”

The episodes remaining in the contract were filmed and aired, and the show disappeared from the screen with little fanfare. Serling’s only television series with a continuing character had been a commercial failure. Given time the series may have found a decent following, but by early March of 1966, The Loner was little more than a postscript in the careers of all involved.

“I’m sure Rod was very hurt by the cancellation,” says Bill Self. “It was his old network. It wasn’t given a fair shot in his judgement and in mine. It was very hard for Rod. The critics were against him and his network was against him. It hurt him a great deal.”

Indeed, although his career as a writer of both episodic television and motion pictures would continue beyond The Loner, the majority of Serling’s success and recognition was behind him. Although his contract with CBS required he produce nine pilots in three years, Serling never again turned in another script to the network. With the exception of reruns, CBS never again aired his work.

Serling died of complications following heart surgery in 1975. He was 50 years old. His career and life as dramatist, cultural icon and social commentator is celebrated the world over. Organizations such as the Rod Serling Memorial Foundation (www.rodserling.com) promote and preserve his work while websites such as The Twilight Zone Archives (www.twilightzone.org) and The Twilight Zone Site (www.thetzsite.com) provide visual and informational resources.

Lloyd Bridges went on to work in two other television series and numerous guest roles, but his primary success came in a wide variety of movie roles. Displaying a deft comedic touch seldom used in his early career, Bridges is perhaps best known as a substance abusing flight controller in the 1980 hit Airplane, or as the elder Mr. Mandelbaum in a reoccurring role on the Seinfeld series. Lloyd Bridges was active into the final years of the twentieth century and passed away in 1998 at the age of 85.

As for The Loner, infrequent reruns have relegated the show to general obscurity. It never entered the public consciousness as The Twilight Zone has. There are no Loner comic books or lunch boxes, no William Colton plastic cap pistols, and none of the merchandising that accompanies the successful Westerns of the period. This suits The Loner well, as it was never intended to be a children’s show or a pop culture phenomenon.

In the late eighties, Ithaca College (where Serling taught writing in the final years of his life) ran a radio retrospective of Loner scripts. A compact disc containing Jerry Goldsmith’s complete scoring for the series was also recently released. Aside from this, The Loner exists only in sporadic airings and buried in the yellowing pages of old television guides.

Perhaps if it had aired sooner, at the height of the television Western craze, the series would have been given the chance to succeed. Or if it had premiered later, in the late sixties or early seventies, it might have garnered widespread acceptance among America’s youth. For that was the time when the show’s issues of race, injustice and the futility of war were at the forefront of public awareness due to the Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam.

If The Loner leaves behind any legacy, it is the memory of a show that featured a hero that one could believe in as well as root for. In a genre rife with formula and predictability, it momentarily transformed the cowboy from a caricature to a thinking, and feeling, human being. For that alone it deserves some measure of recognition and respect.

EPISODE GUIDE

THE LONER

1965-66

Greenway and Interlaken Productions

in association with Twentieth Century-Fox Television

Aired on the CBS Television Network

Created by Rod Serling

Produced by Andy White

Starring Lloyd Bridges as William Colton

Director of Photography: Howard Schwartz

Theme music by Jerry Goldsmith

AN ECHO OF BUGLES

Airdate September 18, 1965

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Alex March

Music: Jerry Goldsmith

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Tony Bill……………Jody Merriman

Whit Bissell………………….Nichols

John Hoyt……………………Colonel

Lou Krugman……………..Bartender

Stephen Roberts………………Doctor

Gregg Palmer………………..Adjutant

A swaggering gunfighter targets an aging

Confederate veteran, and Colton steps in

to deal with the bully.

THE VESPERS

Airdate September 25, 1965

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Leon Benson

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Jack Lord………..Reverend Booker

Joan Freeman…………Alice Booker

Ron Soble…………………..Deneen

Bill Quinn……………………Doctor

Sworn to avenge his brother’s death, a hood

comes gunning for a small town’s local minister.

When Colton arrives to warn his old friend

and ex-soldier, he finds the man unwilling

to resort to violence to protect himself

and his pregnant wife.

THE LONELY CALICO QUEEN

Airdate October 2, 1965

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Allen Miner

Music: Nelson Riddle

Film Editor: Hugh Chaloupka

CAST

Tina Hermensen………………Angie

Jeanne Cooper………………..Marge

Edward Faulkner…….Bounty Hunter

Tracy Morgan………………Francine

Lyzanne LaDue…………………Ruby

Breena Howard……………..Suzanne

A dance hall girl mistakes Colton for her mail-order bridegroom.

THE KINGDOM OF McCOMB

Airdate October 9, 1965

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Leon Benson

Music: Nelson Riddle

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Leslie Nielson……………..McComb

Tom Lowell………Young Townsend

Ken Drake…………….Townsend, Sr.

Ed Peck……………………..Lowden

Robert Phillips…………………Sloan

Unable to perform the deed themselves,

a group of religious colonists attempt to recruit

Colton to kill a powerful landowner for trying to evict them.

ONE OF THE WOUNDED

Airdate October 16, 1965

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Paul Henreid

Music: Jerry Goldsmith

Film Editor: Hugh Chaloupka

CAST

Anne Baxter………….Agatha Phelps

Lane Bradford………………Gibbons

Paul Richards………..Colonel Phelps

Steve Gravers……………………Doc

Colton tries to help a Union army veteran

left mute and immobile by the psychological

horrors of war.

THE FLIGHT OF THE ARCTIC TERN

Airdate October 23, 1965

Written by Andy White

Directed by Don Taylor

Music: Nelson Riddle

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Janine Gray…………………Terna

Tom Stern………………Rob Clark

Larry Ward………………….Monte

Colton becomes involved in a romantic triangle

when he saves a friend’s bride-to-be from a runaway horse.

WIDOW ON THE EVENING STAGE

Airdate October 30, 1965

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Joseph Pevney

Music: Nelson Riddle

Film Editor: Hugh Chaloupka

CAST

Katherine Ross…………….Sue Sullivan

Lloyd Gough…………….Harry Sullivan

Bill Zuckert………………………Stinnet

Alan Baxter……………………..Driscoll

Ann Staunton……………Esther Sullivan

Rafael Lopez…………….Indian Captive

John Damler………………….Stableman

Following the murder of a man during an

Indian attack, Colton witnesses a town’s

prejudice towards the man’s Indian widow.

Katharine Ross and Lloyd Bridges

THE HOUSE RULES AT MRS. WAYNE’S

Airdate November 6, 1965

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Allen Miner

Music: Nelson Riddle

Film Editor: Hugh Chaloupka

CAST

Nancy Gates…………….Mrs. Wayne

Lee Phillips…………………..Gibson

Lindy Davis……………Jamie Wayne

Dick Wilson……………….Bartender

Jonathan Kidd…………………Barber

While trying to defend his wife’s honor,

a friend of Colton is killed…and Colton is torn

between seeking justice and keeping his word

to turn the other cheek.

THE SHERIFF OF FETTERMAN’S CROSSING

Airdate November 13, 1965

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Don Taylor

Music: Nelson Riddle

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Allan Sherman…Walter Peterson Tetley

Harold Peary…………………..Peabody

Robin Hughes……………….Carruthers

Dub Taylor………………………….Jim

Hank Patterson……………….Bartender

Colton has second thoughts after accepting

the position of deputy to a dubious sheriff

of a sleepy Montana town.

THE HOMECOMING OF LEMUEL STOVE

Airdate November 20, 1965

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Joseph Pevney

Music: Nelson Riddle

Film Editor: Hugh Chaloupka

CAST

Brock Peters…………..Lemuel Stove

Russ Conway………Sheriff Simpson

Don Keefer………………….Minister

Charles Fransico……………….Paine

Berkeley Harris……………..Dechter

John Pickard…………….Blacksmith

Colton befriends a Union soldier

who returns from war to find that his father

has been lynched by pre-Ku Klux Klanners.

WESTWARD, THE SHOEMAKER

Airdate November 27, 1965

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Joseph Pevney

Film Editor: Hugh Chaloupka

CAST

David Opatoshu……Hyman Rabinovitch

Warren Stevens…………..Charlie Parker

When a well-intentioned immigrant is stripped

of his nest egg in a rigged card game,

Colton takes on the con artist himself.

THE OATH

Airdate December 4, 1965

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Alex March

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Barry Sullivan………..Dr. Bohan

Joby Baker……………Billy Ford

Viviane Venture……………Maria

When a doctor proves to be as full of whiskey

as he is of self-pity, Colton himself must

perform an emergency appendectomy

on a young gunfighter.

HUNT THE MAN DOWN

Airdate December 11, 1965

Written by Milton S. Gelman

Directed by Tay Garnet

Music: Nelson Riddle

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Burgess Meredith………..Scidry

Tom Tully………………Shaftoe

Jason Wingreen…………..Lucas

Bert Freed………….Sheriff Ross

James Drum……………….Merv

Colton is drafted to help a posse hunt down

a seemingly harmless recluse.

ESCORT FOR A DEAD MAN

Airdate December 18, 1965

Written by Robert Lewin

Directed by Norman Foster

Music: Nelson Riddle

Film Editor: Harry Coswick

CAST

Sheree North……………….Cora

Corey Allen……………….Drake

Jack Lambert……………Libbett

Hal Lynch………………Copley

Thomas E. Jackson…..Old Man

Sal Gorss…………….Ferguson

A man who has deserted the Army wants

Colton to escort him back to his fort.

THE ORDEAL OF BUD WINDOM

Airdate December 25, 1965

Written by Norman Katkov

Directed by Paul Henreid

Music: Fred Steiner

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Sonny Tufts………Barney Windom

Jeff Bridges………….Bud Windom

Allen Jaffe……………..Sid Loomis

Bryan O’Byrne………………Editor

A murder suspect’s son makes life difficult for Colton

when the boy tries to clear his father’s name.

TO THE WEST OF EDEN

Airdate January 1, 1966

Written by Ed Adamson

Directed by Allen Miner

Music: Nelson Riddle

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Ina Balin……………..Trina Lopez

Zalman King…………..Red Segus

Stewart Moss………Hank Prescott

While traveling across the desert to deliver

horses to their new owner, Colton reluctantly

agrees to escort a young woman across the arid land.

MANTRAP

Airdate January 8, 1966

Written by Gerald Sanford

Directed by Allen Miner

Music: Alexander Courage

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Bethel Leslie………..Ellen Jameson

Pat Conway……………….Ballinger

Melville Ruick………………….Jess

Colton becomes the target of an assassination

when he is the sole witness to a robbery and murder.

A LITTLE STROLL TO THE END OF THE LINE

Airdate January 15, 1966

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Norman Foster

Film Editor: Harry Coswick

CAST

Dan Duryea………..Matthew Reynolds

Robert Emhardt……..Preacher Whatley

Bart Burns……………………Chisholm

Colton neither likes nor respects the man

he has been deputized to protect: a rabble-rousing

preacher who fears death from an ex-convict.

THE TRIAL IN PARADISE

Airdate January 22, 1966

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Allen Reisner

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Robert Lansing…………Hibbard

Edward Binns…………….Manet

Curt Conway…………….Dichter

Joe Mantell……………Allerdyce

Deanna Lund……………..Susan

Colton provides the defense in a kangaroo

court trial of a former Union Army officer.

A QUESTION OF GUILT

Airdate January 29, 1966

Written by Les Crutchfield

Directed by James B. Clark

Music by Nelson Riddle

Film Editor: Harry Coswick

CAST

James Gregory………..Major Crane

Jean Hale……………Myra Bromley

Phil Chambers……………Bartender

Frank Gerstle…………………Miner

In the darkness Colton kills an intruder,

and discovers the man is an Army Lieutenant.

THE MOURNERS FOR JOHNNY SHARP part I

Airdate February 5, 1966

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Joseph Pevney

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Beau Bridges……………Johnny Sharp

James Whitmore……….Doc Fritchman

Pat Hingle…………………Bob Pierson

Joyce Van Patten………………..Peggy

John Doucette………………..Benneke

G.V. “Skip” Homeier…………..Philby

While a young gunman lies dying in a cave,

a ruthless man waits outside hoping

to get his hands on the boy’s loot.

THE MOURNERS FOR JOHNNY SHARP part II

Airdate February 5, 1966

Written by Rod Serling

Directed by Joseph Pevney

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Beau Bridges……………Johnny Sharp

James Whitmore……….Doc Fritchman

Pat Hingle…………………Bob Pierson

Joyce Van Patten………………..Peggy

John Doucette………………..Benneke

G.V. “Skip” Homeier…………..Philby

Following the late Johnny Sharp’s instructions,

Colton has arranged for the four people

who were closest to the gunman to meet

at the undertaker’s parlor.

INCIDENT IN THE MIDDLE OF NOWHERE

Airdate February 19, 1966

Written by Andy White

Directed by Joseph Pevney

Film Editor: Harry Coswick

CAST

Mark Richman……………Conway

Beverly Garland…………..Colores

Cindy Bridges………………Wendy

George Ramsey………………Cook

Lennie Geer……………..Lawman

Colton encounters a girl riding a horse

stolen during a stagecoach robbery and

is led to her villainous father.

PICK ME ANOTHER TIME TO DIE

Airdate February 26, 1966

Written by Ed Adamson

Directed by Alex March

Film Editor: Harry Coswick

CAST

Martin Brooks…………Chris Meegan

Ed Peck………………………..Charlie

Lewis Charles……………………Pete

Joan Addams……………Jean Cantrell

Mike Mazurki……………Rule Vernon

Steven Darrell…Sheriff Walter Cantrell

Colton is accused of slaying a sheriff.

THE BURDEN OF THE BADGE

Airdate March 5, 1966

Written by Norman Katkov

Directed by Larry Peerce

Film Editor: George Gittens

CAST

Victor Jory………………Simon Ridley

Lonny Chapman………..Chad Mitchell

Eloise Hardt…………..Martha Mitchell

Dorothy Rice………………………Ann

John Daniels……………………Jimmy

Bill Henry………………………….Ben

Bill Hart……………………………Vic

Buff Brady…………………………..Ed

A group of ex-criminals deputize Colton

to defend and protect them.

TO HANG A DEAD MAN

Airdate March 12, 1966

Written by Milton S. Gelman

Directed by Alex March

Film Editor: Harry Coswick

CAST

Bruce Dern……………….Merrick

Beverly Allyson…….Maria Flores

Colton joins a sheriff in search of

a town’s destroyers.

![]()