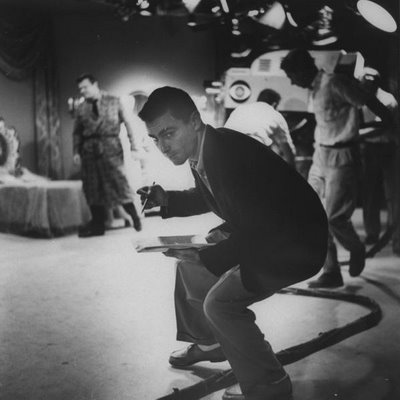

Golden Age: A young Rod Serling tiptoes over camera cables during a live production at CBS

Beyond the Zone: Tony Albaralla reviews obscure productions from Rod Serling’s career

“Slow Fade to Black”

Bob Hope Presents

The Chrysler Theatre

Aired: March 27, 1964

Starring Rod Steiger, Robert Culp, Sally Kellerman, and Anna Lee

I recently made an appointment at the Paley Center in New York to screen three Serling teleplays. I had previously read the scripts for two of them “The Rack” and “Noon on Doomsday,” both United States Steel Hour productions–so although I never saw this pair, I knew what to expect, and enjoyed them greatly. The third screening was “Slow Fade to Black” and I came in on it relatively cold, knowing little of the episode beyond the cast and the barest of plot descriptions. I enjoyed this teleplay even more than the first two. I was so impressed that I decided it should be the subject of this inaugural installment of “Beyond the Zone.”

Armed with only a story synopsis, I went in expecting this to be a riff on “Requiem for a Heavyweight”—I.E., another over-the-hill character, put out to pasture with little or no concept of how to function outside his own secluded world. This element exists in “Slow Fade to Black” but is not the focus. Here, the main character does not “go gentle into that good night” but rather claws and fights and manipulates in his struggle to survive.

Rod Steiger stars as Mike Kirsch, a single-minded and aging movie mogul who has lost touch with the state of modern moviemaking. With all his attention, passion, and love invested in his studio, he has neither need nor patience for his wife and daughter, whom he alienated years ago. His arcane approach has cost his studio millions in recent years, yet Kirsch cannot adjust to the changing times. He continues to cling to the belief that the way out of the hole is to produce a movie that harkens back to the old days, a film that is not afraid of sentiment, that has mother in it, has the American flag and ice cream cones, not the agony you see today.”

Steiger overacts in typical fashion, but not as much as usual, and his delivery is not as hysterical as it was in Serling’s earlier script for Playhouse 90, “A Town Has Turned to Dust.” In fact, the slight over-exaggeration of expression actually fits his anachronistic character quite well. Cutting, bombastic, and irascible, Kirsch is very much a product of an earlier Hollywood era. “We’re a couple of old men who built something, watched it grow, nursed it along,” a fellow studio executive of similar age explains to Kirsch. “So this is the way it goes. Somebody’s always around the corner. Somebody younger, ready to take it away.” Kirsch will have none of it. He berates this contemporary, sneeringly dismisses the man’s argument for retirement, and turns his back on his longtime friend.

Mike Kirsch is an amalgam of several Serling characters. He’s Andy Sloane, from “Patterns,” the worn out executive who will not exit the stage; he’s Martin Sloan, the empty and restless media man in “Walking Distance;” he’s Randy Lane, the lonely, past-his-prime salesman in “They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar.” Kirsch’s closest parallel is probably Ernie Wigman, the aging bar owner who struggles to maintain his hold on life, a character from another Serling-scripted Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre entry, the 1963 Emmy-winning “It’s Mental Work.” Of all these characterizations, Mike Kirsch is the most cynical, the hardest-edged, the most obstinate, and the most alone.

The character is established early on, when Kirsch must intervene when an actress refuses to work until she is given more money. He offers her a thousand dollars a week more, then confronts her agent (in the first of several Serlingesque monologues) as he exits the set: “And one more thing, this comes to you from me, mister agent; Don’t bring your dirty smile into my lot, then spit all over contracts you’ve already signed because your client got hungry. I’m going to live to see the day when it will be like the old times, Wessler—when a bloodsucker like you comes through the front gate, I’ll have the guard throw you right out on your can.”

In a pivotal boardroom scene, Kirsch is asked by a group of stockholders to resign. They own controlling stock in the company, and if he refuses to leave, they promise to oust him in a vicious proxy fight. Kirsch believes his best chance of fending off this attack is to score a box office success, and he hurriedly calls a meeting with investors and his trusted young assistant, Peter Furgatch, to try to sell a script he feels is perfect for the occasion.

Furgatch is played with wonderful subtlety by Robert Culp. Furgatch is to Kirsch what Fred Staples is to Andy Sloane in “Patterns”—a friend, a confidante, and an eventual replacement. And like Staples, Furgatch is a complex character who is torn by a sense of loyalty to his mentor, a hunger to get ahead, and the realization that his over-the-hill boss cannot function in the best interests of the company. When Kirsch pitches his movie idea and asks Furgatch to back him up with an enthusiastic assessment that the young man does not share, Furgatch is obligated to give his honest opinion.

“It’s vintage stuff,” Furgatch reluctantly admits, “with oversimplified moments, much too much sentiment, very little subtlety. It’s the kind of thing that went well with a piano and a ten-cent ticket, and in its day it probably would have given the audience its money’s worth. So did Maxwell cars, but you don’t run them in competition today.” Kirsch, angered and feeling betrayed, fires Furgatch.

Kirsch returns home to his last chance at salvation: Gerry, his emotionally estranged but financially obligated daughter. (Kirsch pays for her apartment and luxurious lifestyle, and she resents him for it and for neglecting her and her mother in every other facet of life beyond the monetary). Gerry—another of this episode’s marvelous performances, this one by Sally Kellerman—owns enough company stock (a one-time gift from her father) to allow Kirsch to regain controlling interest, and he asks her to sign it over to him.

When she balks, he demands the stock. Paula Kirsch (Anna Lee), Gerry’s mother and Mike’s subservient, habitually drunk wife, is present at the argument, but refuses to defy her husband. When Gerry tells her father she will consider his request for the stock, he threatens her, in the following exchange:

|

MIKE

|

| You think about this. I have enough on you to burn you from Hell to breakfast. You think about your weekend drunks when you were eighteen years old, and you think about two trips to the doctor when you were still in college. Now you think about that! |

|

GERRY

|

| Hey, Mike, do something for me, will you? Remind me that you’re my father. |

|

MIKE

|

| Don’t talk to me about fathers and daughters. Don’t do that to me. The only flesh tie I have is one hundred acres of movie studio that makes film. That’s my heart, out there, that’s my flesh! |

The next day, Kirsch returns to the studio to find that the current production has ground to a halt because the lead actress has again refused to work. He storms on set and smashes a tripod-mounted spotlight to get her attention.

|

MIKE

|

| Vanessa, I just cost the studio fifty-six dollars. You triple that twenty-odd times and you get some idea of what you’re costing the studio. |

|

ACTRESS

|

| Michael, Dear Heart, I don’t care how much I’m costing the studio. All I can say is that this script still stinks, and I’d be dishonest in playing it the way it is. |

|

MIKE

|

| Sweetheart, you’re dishonest every time you deposit your salary. You get $500,000 a picture and ninety-nine and nine-tenths percentage of it is because of your measurements, not your talent! |

|

ACTRESS

|

| You keep it up, mister, and you’re going to find yourself fresh out of one actress. |

|

MIKE

|

| Well, you point her out to me. You couldn’t come up with an honest cry if you had an onion in your mouth. Now I’m going to tell you something, dear lady, if I’m hurting your feelings, I tell you what you do. You get on the phone, you call your lawyer, call your agent, call your accountant, call your mama, and tell them this: You say that Mike Kirsch runs this studio, and from now on we are shooting pictures with actors that are actors, not people that are worried about capital gains! |

Kirsch returns home and is confronted by Gerry, who informs him that she has signed her stock over to his opponents. To his stunned, silent reaction:

|

GERRY

|

| The ship is sinking but the mogul remains steadfast on the poop deck, lashed to the anchor. |

|

MIKE

|

|

(coldly)

|

| From a stranger in the street, I could expect more understanding. |

|

GERRY

|

| Correction, Mr. Kirsch, a stranger in the street can go home, or call a cop, or wake up. My nightmare is twenty-eight years old. It’s all about a movie Mussolini who used to keep a riding crop on his desk. And every time he wanted to knock down an actor, or lay out a producer, or bulldoze an agent, he’d slam that riding crop down on the desk. |

|

PAULA

|

| Oh, Gerry, Darling, no! |

|

GERRY

|

| What’s the matter, mother, have you lost your memory? He took a beautiful, gentle woman and turned her into a ghost. And me a sick little tramp who tried hitting back by rolling in the mud. You better believe it, papa, there hasn’t been one single, solitary thing I haven’t done that wasn’t aimed at your jaw. |

|

MIKE

|

|

And what about me, Gerry? Did I ever turn my back on you?

|

|

GERRY

|

|

Last night you were willing to kick me into the sewer for a couple of concrete buildings and a film lab! Well, papa, I’ve had more love on a weekend binge with a nameless drunk than I’ve had in a lifetime in this mausoleum!

|

Mike retreats to the balcony, but Gerry follows him, explaining her decision to put him out of business by selling her stock to his detractors:

|

GERRY

|

| Chalk that up along with my affairs, my little peccadilloes, the other embarrassments—how about it, Mr. Kirsch? You want to send out for your riding crop? |

|

(at his silence)

|

| Hey, Mr. Kirsch, make yourself known! It isn’t you, is it? This must be a stand-in. Kirsch would have chopped off heads, pulled down draperies. Mike Kirsch would have yelled “Cut!” and we’d have to disappear! Well, believe me, I would love to disappear. And maybe forget those three make-believe husbands who married me to get close to you, so that at the tender age of twenty-eight years old, I haven’t the capacity to feel love. I can’t believe anyone holding my hand! |

Dejected, Mike retreats to the stairway and begins to climb upstairs. He has to get dressed to attend a dinner, at which he’ll be the recipient of the “Producer of the Year” award (the only real over-the-top moment of irony in the play). As he reaches the foyer, he is greeted by Furgatch, just walking in the door to deliver some news he didn’t want Kirsch to hear second-hand: The studio has terminated Kirsch and hired Furgatch to replace him. Mike’s reply upon hearing this:

|

MIKE

|

| Well, why not? Why shouldn’t I be replaced? I don’t know the business anymore. Shooting pictures I spent forty years of my life doing. But fancy knifing, that I never learned. That I leave up to commandos like you. |

|

FURGATCH

|

| It’s a different time, Mike. Different people. Shooting a different kind of product. You say you got knifed. Maybe. Your kind of man has to get knifed, Mike. You never step aside…we’re no different from what you were forty years ago. We’re trying something new with Cinemascope. Just the way you did it with one-reelers. The only difference in the world between my kind and yours is it’s our turn. |

That evening at the event, with Furgatch and all the stockholders and industry people present, Kirsch is handed his award. He takes the podium to deliver the following:

|

MIKE

|

| Now, to all you Johnny-come-latelies out there, all of you who had this business handed over to you like an inheritance and a legacy; all of you, you who never had to bleed or scramble to give birth to it or keep it alive, let me say this: |

|

There were a lot of people—they couldn’t speak English so good—they paved the way for you. And they broke their backs. And they did it in cellars and they did it in attics, trying to figure out ways to aim the camera so that all of you “Angry Young Men” could say that you were part of an art form.

|

| I’m speaking about people like Jesse Lasky, D.W. Griffith, Mack Sennett; and let us not forget a funny little man with baggy trousers and a nutsy mustache. They had talent, they loved what they were doing, and people loved them for doing it. But you don’t love to make movies, and that is a shame. Because you don’t know what you’re missing. |

The episode closes with Kirsch alone in a screening room, weeping, and watching an old silent movie that he asks the projectionist to run over and over again. His career and his studio were his identity and his life, and came at the price of his family. Now he has lost everything.

“Slow Fade to Black” is a powerful story, expertly acted and beautifully written. It is dynamic and direct, yet sprinkled with subtle moments, such as Kirsch reaching for the Oscar on his mantle and finding it covered with dust, or when Kirsch calls to a grip in the rafters of a set, knowing him—one of his lowliest employees—by name. Playhouse 90’s “The Velvet Alley” featured a writer engulfed in a crash-and-burn Hollywood tragedy, and Twilight Zone’s “The Sixteen-Millimeter Shrine” essayed the decline of the movie industry from the perspective of an aging actress; “Slow Fade to Black” fuses the two—and pulls no punches in doing so.

![]()